After learning that Japanese beef was graded with a two dimensional system (A, B, C and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), I had thought I could work on the reason behind the different grades in tea (the most known being in the former English colonies and only for black teas).

To do so I began looking in my books on tea for evidences on why this system was in use and how it the other tea producing countries that did not follow it dealt with this topic. Let us just say for now that the other system combines geographical references and ways of preparing tea to produce a certain quality. However, I stopped when I found out a small reference about the tea produced in Tanzania, which had its origin in German colonisation.

I know the context nowadays is complicated to speak about such part of history and without ignoring the consequences of such occupation, I would like to focus on a small part of it: the introduction of tea.

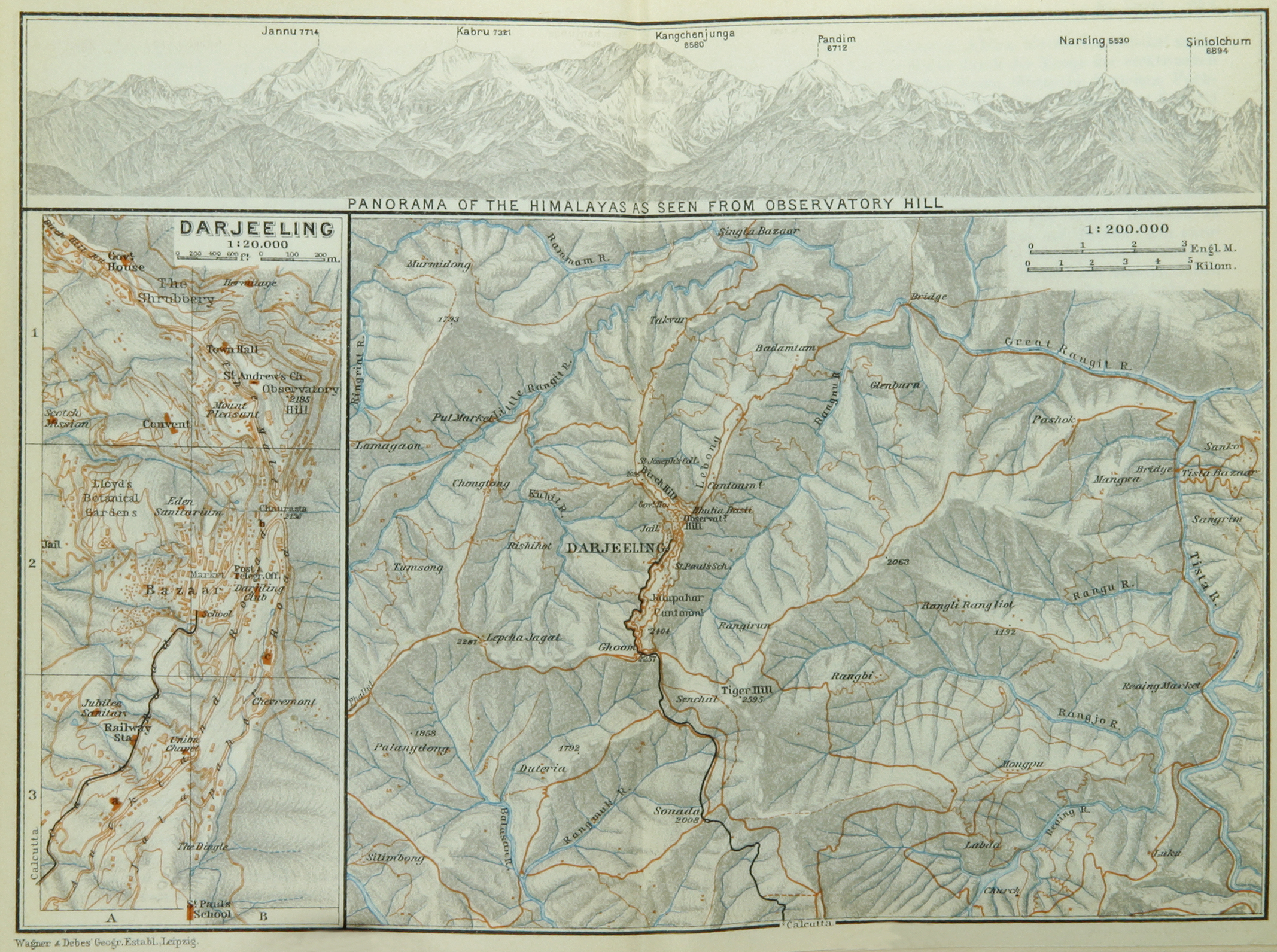

As with most European countries (see there), Germany developed an approach based on an Agricultural Research Station in Anami that was grounded in 1902 and taken over by the British in 1920 when they were awarded that part of the former German East Africa. Although this research centre had a good reputation (for coffee or for its botany garden) as stated by William Nowell, new Director of the East African Agricultural Research Station “As you are all doubtless aware, we occupy the site and buildings of the Biological and Agricultural Institute, founded in 1902, which under the direction of the late Dr. Zimmermann rendered most valuable services to the colony of German East Africa. […] but we inherited a valuable library, a considerable herbarium, and plantations stocked with introduced economic plants.” (Proceedings of the Royal Society of Arts, Dominion and Colonies Sections from 24th October, 1933), the British fired all its personal, probably out of fear that they would not be loyal to the Crown (the kind of things that was important in those years).

It seems that the first tea was planted in 1904 but didn’t leave the realm of experimentations before the second half of the 1920s (a recurring problem in these research stations be they in India or in Indochina is how long it took from experiments to real “commercial” use, perhaps a topic for another time). To increase the spread, a tea officer was appointed (I still need to find out what this is) and free seeds were given between 1930 to 1934 with a tea factory opening in 1930.

In 1934, 1,000 ha had been planted, producing 20 tons of processed tea, of which 9.3 were exported (Carr et al. 1988, Tea in Tanzania, Outlook on Agriculture, 17:18-22). I do wonder what happened to the remaining 10.7 tons. Were they drank in Tanzania? This seems quite unlikely.

The outbreak of World War II brings us another information as because of the presence of many German settlers (which must have returned after World War I or decided to remain), the British government decided to dispose them of their estates, which were acquired by a subsidiary of Brooke Bond, an English tea brand famous for PG Tips). The land must have been good for tea as the company began to plant more tea (the final results being that in 2010 29,000 tons produced of which 28,000 were exported).

However and surprisingly enough, some Germans were still there as I found out that a Mr Voigt, last (probably because of its age but I couldn’t find any other information on that part) German tea grower in the area retired in 1986 after 60 years living in Tanzania. He even wrote a book about his life, 60 Years in East Africa: Life of a Settler 1926 to 1986. I guess it contains some information on these plantations and how they fared through the years and could be compared to similar experience from British settlers in Kenya or Assam around the same time.

The question I didn’t answer was how did I learn about the grading of Japanese beef. Did you see my title? It is from a classical 1968 war movie with Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood about a “secret traitor” stuff and I thought it fitted the topic of this post to a T, so I selected it.

What? I didn’t answer the beef question… Let’s save it for another time.

We all know about Robert Fortune and the British East India Company (for a really small summary, you can look

We all know about Robert Fortune and the British East India Company (for a really small summary, you can look  What is a Wardian case? It is a sealed container protecting the plants or the seeds that needed to be protected from salt, moisture… yet at the same time needed light, water… because it is a living being that can’t live without food, water, solar light. Through its glass top, it allowed the light to get in and the closed container allowed humidity to develop, humidity that gave the plants the water they need.

What is a Wardian case? It is a sealed container protecting the plants or the seeds that needed to be protected from salt, moisture… yet at the same time needed light, water… because it is a living being that can’t live without food, water, solar light. Through its glass top, it allowed the light to get in and the closed container allowed humidity to develop, humidity that gave the plants the water they need.

Recent Comments