Following my latest post, I dug a little more into the plantation concept and I received some more information from a couple of people, so here is the follow-up.

According to the Tea Board of India, there are 833 small tea farmers in Darjeeling. I couldn’t get all the information I needed on them to compare them to the data I had but I got something.

For example, 60 of these farmers are gathered in a cooperative with approximatively 23 hectares of tea that aims to produce through its factory 15,000 kilograms of tea per year, which means an average production for the cooperative of 250 kg per tea farmer or 652 kg per ha. I wrote for the cooperative as they might sell it too to others (I have no info on that), which would mean that they could produce more.

When compared to the data available on the Nepalese small farmers (658.27 kg per site, i.e. per tea farmer and 847.43 per ha), the numbers I found for Darjeeling are much lower, meaning either a lower productivity per hectare (and coming back to the “problems” of older trees) or a willingness to produce less for higher quality or because of a more sustainable approach. However, this data is only on a small sample and might not be representative of the overall picture.

So after getting back on track, let’s get back to where we stopped last time and that was speaking about the financial backing needed to go into this business. From there on, I will dig a little more into this financial aspect, go through history/economical politics before trying to see what is specific in the “traditional” model of big estates before checking why would this model fail (if it fails that is).

Tea estates like most of the plantation crops can trace their roots to the 19th century (even if some were there earlier because of being cultivated during and fuelling the European colonial expansion). And like all of them, tea production was hit by a drop in demand and therefore in price (since they hadn’t foreseen it, there was an overproduction) during the crisis following Black Tuesday (the Wall Street Crash of 1929).

“There have been attempts to restrict tea production in the past. In the world recession of the 1930s, tea prices fell dramatically. This prompted the major producers – India, Ceylon and the Netherlands East Indies – to enter into International Tea Agreements, which restricted production to 85 per cent of normal.i”

The obvious results of both the crisis and the reduction in production was that only those with cash could go through these years, leading to a further concentration as those without cash were absorbed and the small holders went to other crops that allowed them to eat or to gain more cash, just like in the Netherlands East Indies (http://teaconomics.teatra.de/2014/08/22/rise-and-fall-and/) or simply did not have the cash to withstand the decline in pricesii

Following the independence of India and as in most countries going through the same process, there was a wave of nationalisation of key sectors but the effects on tea were not those that could have been expected.

“Following on independence, the Indian government began to plan extensive nationalization of key industries. Tea featured in some of the recommendations, and many British companies took fright and began to run their estates down. They spent as little as they could on maintenance and renewal […] They also sold some estates to Indians. […] This catalogue of attacks on the British tea interest might have been expected to drive it out of India. However, it proved remarkably resilient. The companies that were sold were, in general, those with the poorer land or less successful management. The yield on the remaining British estates remained consistently higher than on the Indian-owned estates so that, although acreage fell, production was proportionally less affected.iii“

This extract explains why nationalization didn’t mean the end of foreign controlled estates (which were still among the big players) or a rise in the support for small holders since the only known development models were focusing on productivity and heavy industry.

Furthermore, as in most independent countries, India focused on national development with protectionism and a premium to national industries (I don’t forget the Green Revolution but since I didn’t find any evidence that it had an impact on the tea industry I can’t be 100% sure about it).

“In the new tariff regime, investment costs sharply increased in businesses that relied on imported equipment, including tea.iv”

As you can guess, all this combined meant that more cash was needed to invest in tea, to produce and “manufacture” tea, which meant that small farmers couldn’t efficiently compete.

In the previous lines, I spoke a lot about India and the independence process but not at all about Nepal. You might ask why. Simply because before 1951, Nepal was closed to foreigners and avoided as much as possible any contact with them (this was seen as a way to keep its independence).

After 1951, Nepal undertook a series of Five-Year Plans to develop first its infrastructures and communication and then agriculture (with cash crops being given priority in the Fifth Plan running from 1975 to 1980).

The situation and priority changed later on in both countries in the recent years and small tea farmers now have the support of both governments as can be seen in the most recent position and strategy papers in both countries.

“To attain the above position of tea industry in Nepal in 2020, the following strategies need to be adopted:

[…]

-

Provide support to small tea farmers for preparation of loan scheme and application and assist in the availing of credit from ADB/N and Commercial Banks.v“

Why this change? The reason is simple. It is thanks to the new trends in consumption (smaller production, more authentic/sustainable/fair products). Small farmers are seen as those able to satisfy this demand; perhaps thanks to a higher motivation? Or to a certain ease to change their production processes?

Does this mean that in the modern consumption world, the small farmers model is more efficient? Once you have left the financing/investment aspect, what is left of the “sheer logistics of the old model” as said by Lazylitteratus in his original post? Does it make the old model inefficient?

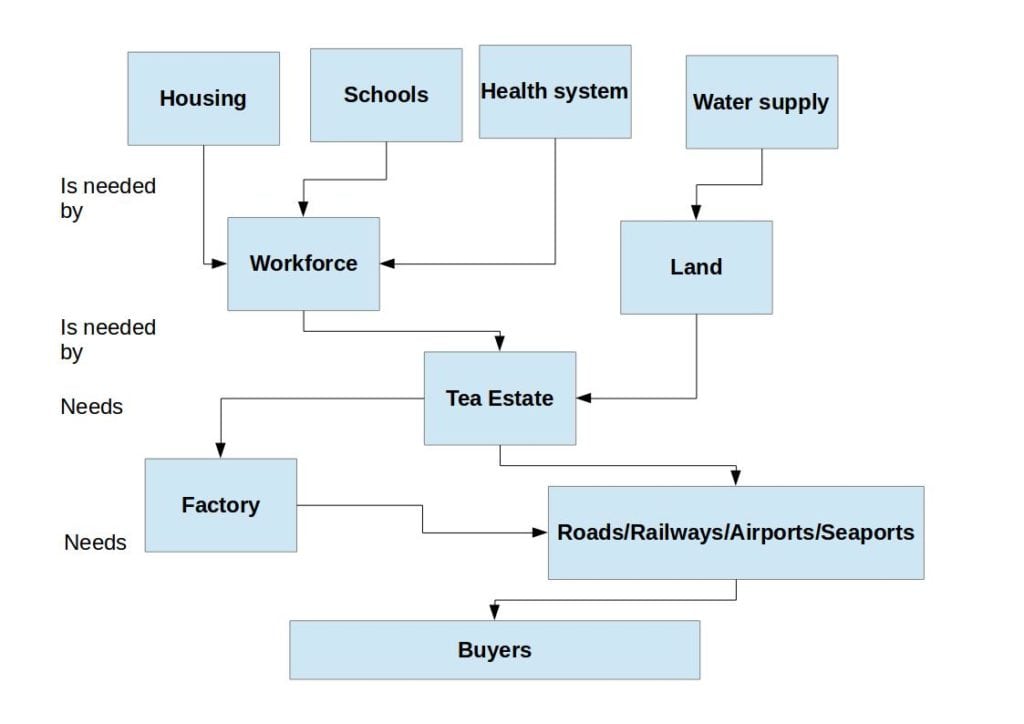

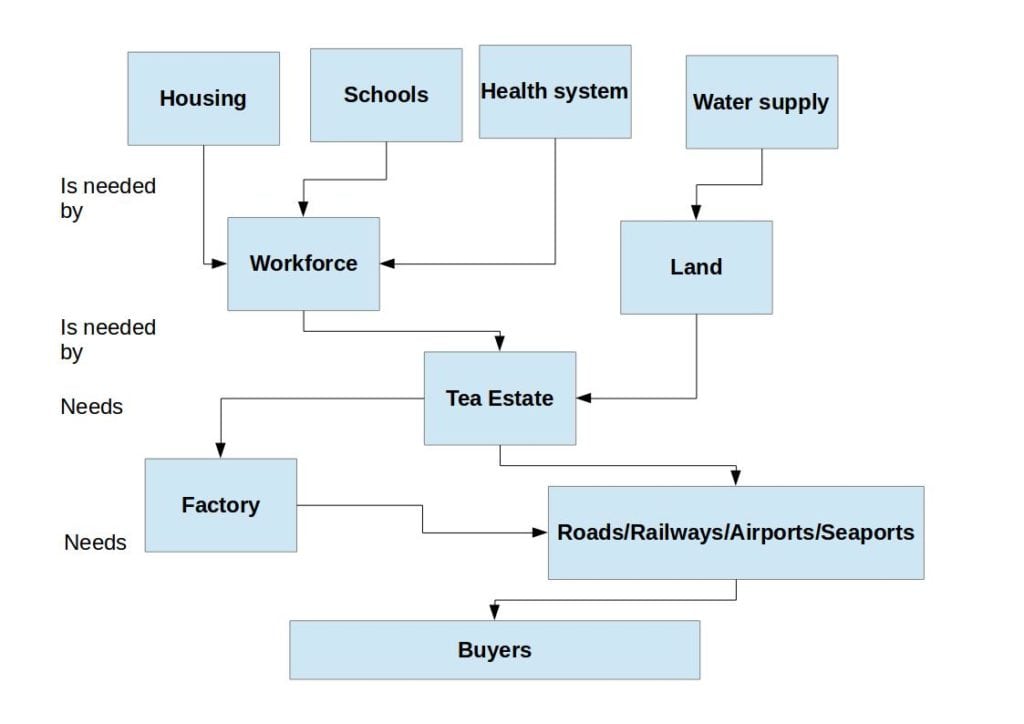

We have seen that size, production and productivity set both models apart but the fundamental difference could lie in what makes the tea production system.

What I mean by system is everything needed to produce tea and to sell it. Since a picture is worth a thousand words, here is an oversimplified drawing of what I see as the tea production system.

The tea production system

To again simplify things, there are three main suppliers of these services, the private sector, the public one and a mix of both.

Factories are needed to produce tea and they are linked to an estate or a company like in the “old” model (but smaller farmers can be allowed to have access to it) or linked to a State initiative or to a cooperative (backed or not by an estate).

Schools and infrastructures are something that the State has to provide. They can both benefit from private “help” or sponsorship but the final provider remains the State, which means that everyone, all around the country has to pay for it.

“There are three schools […] they belong to the Indian government. The estate has nothing to pay to keep them operating (apart from a few repairs now and then). Furthermore, the registration is not really free as the family must pay 250 rupees per year. Like the health system, these measures are mandatory by Indian law.vi”

Health and housing should be provided by the estate but the situation depends on the estate and evidences are not so clear as to who pays what and why (hence why I won’t say anything further on this topic). In theory, the Indian law make a free health system mandatory for the workers of the organised sectorvii. This means that for health and housing the estate should pay something (but according to different sources, on some estates, they don’t pay much).

So we saw that most of the things that makes the tea system are either provided by the State or are not really making a huge difference. The only factor left and the reason why the “logistics of the old model” might be failing (unless someone points me to what is lacking) comes from the only thing that we have not studied yet: people.

On an estate, there are two different kinds of people: those working on a temporary basis and the permanent ones, those last one being paid all year long.

|

Permanent workers

|

Temporary workers

|

Total

|

|

Number

|

% of total

|

Number

|

% of total

|

|

Darjeeling

|

2,734

|

62.63

|

1,631

|

37.37

|

4,365

|

|

Terai

|

1,056

|

31.99

|

2,245

|

68.01

|

3,301

|

|

Dooars

|

11,672

|

68.01

|

5,489

|

31.99

|

17,161

|

|

Total

|

15,462

|

62.28

|

9,365

|

37.72

|

24,827

|

Number of workers in the factories in West Bengal in 2004viii

|

Permanent workers

|

Temporary workers

|

Total

|

|

Number

|

% of total

|

Number

|

% of total

|

|

Darjeeling

|

45,919

|

93.72

|

3,079

|

6.28

|

48,998

|

|

Terai

|

23,866

|

65.21

|

12,730

|

34.79

|

36,596

|

|

Dooars

|

135,085

|

88.73

|

17,166

|

11.27

|

152,251

|

|

Total

|

204,870

|

86.14

|

32,975

|

13.86

|

237,845

|

Number of workers in the fields in West Bengal in 2004ix

|

Permanent workers

|

Temporary workers

|

Total

|

|

Number

|

% of total

|

Number

|

% of total

|

|

Darjeeling

|

48,653

|

91.17

|

4,710

|

8.83

|

53,363

|

|

Terai

|

24,922

|

62.47

|

14,975

|

37.53

|

39,897

|

|

Dooars

|

146,757

|

86.63

|

22,655

|

13.37

|

169,412

|

|

Total

|

220,332

|

83.88

|

42,340

|

16.12

|

262,272

|

Number of workers in the tea estates in West Bengal in 2004

As can be seen from the data I found (I know these are official figures and that reality can be different but I had to use some figures), the permanent workers are the most numerous ones, which means that most of the workers are paid the whole year.

To compare those percentages to something, I can tell you that in 1985, the family farms in Gujarat employed 70% of temporary workersx.

This highlights the real difference between both models. It is not as much the investments or the production capacity but rather the way the people are employed and paid that makes the difference.

“In fact, reliance on family labour is usually the main factor explaining why small family farms are more efficient than large ones relying on hired labour which necessitates costly supervision (Muyanga and Jayne 2014,4).xi

I guess this conclusion is not really what we expected.

iTea, Addiction, Exploitation and Empire by Roy Moxham, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004, p.216

iiThe rubber industry: a study in competition and monopoly by P.T. Bauer, Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1948

iiiTea, Addiction, Exploitation and Empire by Roy Moxham, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004, p.207-208

ivTrading Firms in Colonial India by Tirthanka Roy, Business History Review, Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Spring 2014, p.41

vConcept Paper on Study of Nepalese Tea Industry – Vision 2020 submitted by Ajit N.S. Thapa, March 2005

viLes réalités du commerce équitable – l’exemple d’une plantation de Darjeeling by Arnaud Kaba, L’Harmattan, 2011, p.131 (the translation is mine)

viiLes réalités du commerce équitable – l’exemple d’une plantation de Darjeeling by Arnaud Kaba, L’Harmattan, 2011, p.129

viiiLes réalités du commerce équitable – l’exemple d’une plantation de Darjeeling by Arnaud Kaba, L’Harmattan, 2011, p.121

ixLes réalités du commerce équitable – l’exemple d’une plantation de Darjeeling by Arnaud Kaba, L’Harmattan, 2011, p.121

xPatronage and Exploitation by Breman, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1985

xiLarger Plantations versus Smallholding in Southeast Asia: Historical and Contemporary Trends by Jean-François Bissonnette and Rodolphe De Koninck, Conference Paper n°12, Land grabbing, conflict and agrarian-environmental transformations: perspectives from East and Southeast Asia, April 1985

Recent Comments