This post owns much to the work done by Dr Pim de Zwart from the Wageningen University and Research that published in 2016 a paper in The Journal of Economic History on globalization in the early modern era: new evidence from the Dutch-Asiatic trade between 1600-1800.

I couldn’t access his paper (De Zwart, P. (2016). Globalization in the Early Modern Era: New Evidence from the Dutch-Asiatic Trade, c. 1600–1800. The Journal of Economic History, 76(2), 520-558. doi:10.1017/S0022050716000553) but to make it short and according to the Journal of Economic History « This article contributes to the ongoing debate on the origins of globalization. It examines the process of commodity price convergence, an indicator of globalization, between Europe and Asia on the basis of newly obtained price data from the Dutch East India Company (VOC) archives. »

This will probably not speak to a lot of people here but what got my interest were the words “price data” as the Dutch East India Company imported tea from China to Europe and I thought that perhaps some interesting data (from my point of view) were available somewhere and I did manage to find them as Dr Pim de Zwart made them freely available.

He had gathered together the prices of 16 goods imported by the VOC over the years around 1600 to 1800 and their buying price in Asia over the same period and converted them to the same monetary system, which helps comparison (even more when you are dealing with circa two centuries of data and two different geographical areas).

Sometimes, data was non existent (it happens) and sometimes my guess is that there might have been several conflicting information regarding it or for tea (which you probably understood for me explaining the ins and outs was present) as I already found out several names/quality that were shifting through the year.

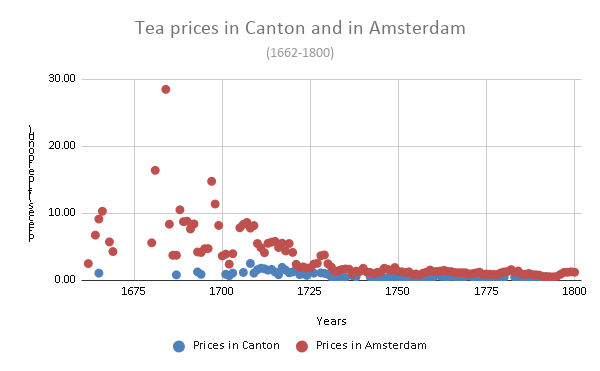

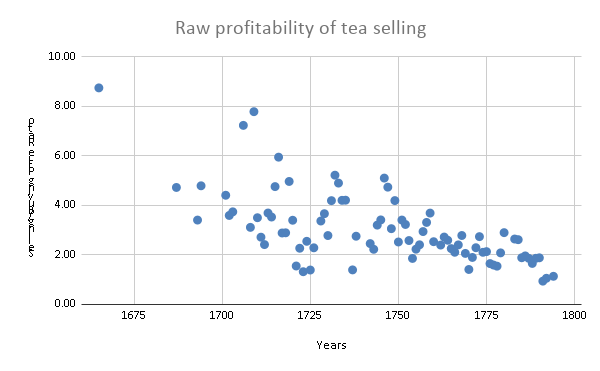

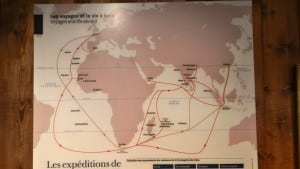

I don’t know how he really dealt with that but I will present you the results below with two charts. The first will show you the selling/buying price of tea over the years (obviously for and from the company store and not for everyday life) and the second is something I called raw profitability of tea selling as Dr Pim de Zwart calculated that ratio (I don’t know why). Me calling it that is an oversimplification of reality as to know the real profitability ratio, you would have to add other costs that are not there like the transport costs, the fixed costs of the VOC for keeping its business operating (and this was a really huge business, just look there at the list of settlements and trading posts it owned and operated like a State) but it gives us some hints about the evolution of the trade as a whole.

But enough talking, let’s go to the charts (you can click on them to have a little more info).

What can we see?

At first (for circa 40 years), tea was a kind of luxury, a product that was rare with high selling prices (and therefore high potential profits). Then the price in Amsterdam began to decrease probably because of increased supply from Asia, be it from the VOC or from competitors, the other India Companies (this was a global race, see for example there or there).

In such a trade war that was raging for all products, what was the likely answer of the VOC (and obviously of the other companies at first)? I don’t know but from what I see here and from what I read elsewhere, it seems to me that they had (and bear in mind that it is my opinion centuries away from the event and with the capacity to use tools and ideas that were unknown by the people at that time, so there is for now for me no way to know if they ever followed a deliberate strategy) few options available as I don’t think (or I couldn’t find any evidence in my readings) there was a real uniqueness perceived by the customer (in other words a ton of a said quality of tea could be delivered by any of the India Companies) and due to the need to generate a lot of money, the VOC couldn’t focus on a single or a few items, which price was likely to drop in case of increased importations.

Because all these companies were focused on only one thing (to say it in simple words going to Asia and getting back from it with a lot of goods and money), because of the path dependence (“we have invested money years after years on this strategy that worked for the others and we need to take gold away from them or prevent them to do so from us”) and because it was also a question of national pride and prestige, no alternative thought on how to act could be at first formulated (once again there is no way of knowing if any deliberate strategy was really devised).

This shows that they were clearly in the conditions described by Michael Porter for his generic strategies. From the picture below that sums up the generic strategies (for a complete overview, go there) and the analysis provided above, the answer to what the VOC and the other had to do is clear

Porter’s Generic Strategies (by Denis Fadeev)

Focus on the costs and aim for the cost leadership.

Is this supported by the facts? If you look closely at the data, the price for the tea in Asia began decreasing around the 1730s (when the VOC was already declining) until it reached a floor between 0.30 and 0.50 fl. per pound.

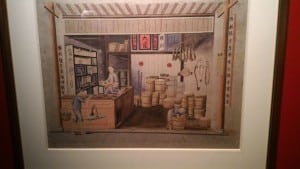

How was this achieved? First, the Dutch imported their goods in Europe through Batavia (today Jakarta) reproducing a model from earlier empires. This meant that everything had first to go though to Batavia being stocked there before being sent to Amsterdam. However since the VOC didn’t have enough ships and people to trade on a “personal” basis, they (like the others before them) used the services of middlemen, Chinese, Indian or Muslim traders that brought goods to Batavia.

Not the optimal solution as these people would likely sell their goods at a higher price but as long as competition hadn’t increase, it was not a problem. However because the British, French and the other India Companies had not access to the network of the Dutch East India Company, they went directly to China resulting in a lower price for them and forcing the VOC to do the same in order to stay competitive.

After an initial drop, the level of price reached a new equilibrium as after getting rid of the middlemen and saving money, the competition between the European companies prevented any further decrease before other approaches were used later in the 19th century.

With this ends for today my quest to find knowledge out of raw information and ends my travel on T.S. Eliot’s footsteps (from a philosophic point of view obviously).

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Recent Comments