This post was prompted by an article I read on the Web about Mac Donald changing the way the Quarter Pounders is made with small steps made in order to improve their quality.

This strategy is called differentiation, trying to make ones product more attractive than those of the competitors to a peculiar target, whether to charge more and make more profit of it or to increase brand fidelity and making it more difficult for people to change from one brand to another.

One of the biggest name in this strategy field is Michael Porter that wrote a lot of books on competitive forces in industries, their impacts and some generic strategies to deal with specific situations.

A picture being worth a thousand words, here is a small look at those generic strategies.

|

Strategic advantage

|

|

Uniqueness perceived by the customer

|

Low cost position

|

|

Strategic target

|

Industry wide

|

Differentiation

|

Offering the lowest prices

|

|

Particular segment only

|

Focus

|

Michael Porter’s Three Generic Strategies

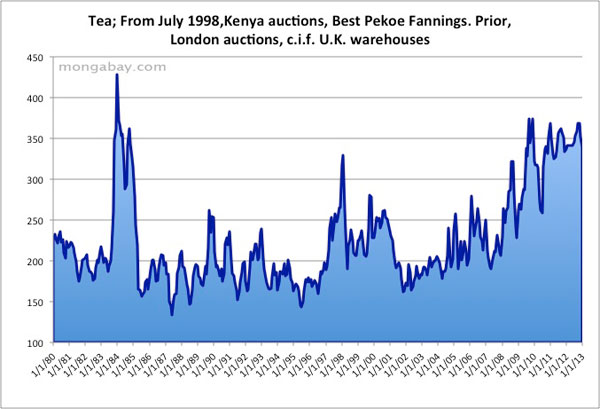

Now, I am sure you are wondering why I am talking about this and what is the link between Mac Donald and tea.

Simple, the idea hit me as I was just looking at this news, could this strategic thinking work in the tea world?

After looking at it, I just had to think that yes, believe it or not, it works (don’t worry things are not cast in stone and without a proper analysis, this might be considered as an oversimplification).

I already wrote things on companies selling speciality teas and what they can do (in strategy and marketing, there is never a definitive and absolute answer), I will summarize what I wrote below before expanding it a little and then looking at the industry wide companies.

Speciality teas companies are usually focusing on a particular segment, trying to be perceived as unique by their customers. The focus on low cost is not something these companies are trying to do as their focus is more on higher quality products, for which people are willing to pay more.

They usually stay “small” and focused on their core business and area of expertise. By small, I don’t mean no growth or something like that but a maximum size in their development (which will change for each company depending on its market, its products…) just before they get into direct competition with the big names and might lose their soul trying to fight against them on their terms.

The other approach is to “grow” but by keeping on targeting new specific needs and markets, which are not overcrowded and where there is no competition (you can call this approach Blue Ocean Strategy or White Space Strategy or even indirect approach (who would have thought that I would one day use a military strategy term for a post on tea?)).

The industry wide companies (call them whatever you want but you know them, don’t you?) have usually focussed on the low cost position on the whole market. After all, their aim is/was to offer the best tea at the lowest price, making a common product of what was before a luxury.

However, faced with increased competition from newcomers while being stuck with a bad image among those willing to pay more for higher quality products (a growing niche market) and yet with a known image for most people as well as a position on the “good quality for the lowest price possible”, these companies had to find an answer and focusing on only one strategy was not the solution as it would have blurred the message/image of the company, changed its profile, leading potentially to a decrease in their market share.

Therefore, they went for a mix between the two strategies, keeping on their low price offer while trying to bring new products on the market (to satisfy the thirst for novelty) and offering different loose leaf teas in nice boxes at a “reasonable” price (thanks to their negotiation power) to try to attract new customers while keeping on with their marketing motto of “good quality for the lowest price possible” (I am not judging the quality of their products here, just trying to explain some things).

You don’t believe this is happening? Just go to your local supermarkets or check on the websites of these companies.

Now, you probably saw three different kinds of products: the good old classical and “basic” offer, some new “innovative” products and the reworked loose leaf classical.

Can this approach be successful? It might thanks to the distribution capacity of such companies and because addressing every need on the market means they might keep their customers (which is always a better and less resource consuming option than conquering new ones) and even attract new ones.

However, if the market seems too big, newcomers might come or be launched by competitors (or the same companies) but the traditional industry wide companies have a secret weapon, their easier access to the retail industry, which allows them to “kill” any competitor trying to attack them straight ahead.

This is a glimpse at the strategies being deployed in the tea industry and its close friend and competitor, the coffee one.

To give a good overview, I had to be synthetic and generic while each company has unique advantages, targets and needs that shape its business and its strategy and with an end result that might be slightly different from what I wrote but without proper data and knowledge of one market and structure, it is difficult to be more precise.

And after all, I promised a quick and oversimplified look at a complex problem, didn’t I?

Recent Comments