Did you know that Al Capone drank whisky in a cup of tea? It might be a hoax but I heard it on a rather serious radio and I found it cool enough to mention it here. A more “serious” reason than the “cool” factor was that it provided a good introduction for the topic of this article.

Some time ago, I asked one of our fellow bloggers here what he would like to see in this blog and his answer puzzled me as he had heard that there was a link between the consumption of alcohol in the United States and of tea and that, the first one was decreasing while the second one was increasing. If you had asked it to me, I would not have come up with a link between these two as it seems completely counter intuitive.

However, I decided to pick up this challenge and to investigate this topic, which was also a perfect way to illustrate one of my latest posts in a practical way.

The first thing was to decide the scope of my data analysis. I decided to go for the three main markets for these two products: America, Europe and Asia (the fact that the sources I later found also had this segmentation is pure luck. You don’t believe me, do you?). I could have gone with several countries but after giving it much consideration, I could not find to which countries, I should compare the United States. Moreover, a focus on one single country might not have been representative of what was going on.

Knowing the geographical area, I decided to check for data.

… … …

… … …

… … …

These were my first results, as it seemed complex to find anything in a single database. I decided to split the search into alcohol and tea and since I knew where to look for tea, I thought it made it easier.

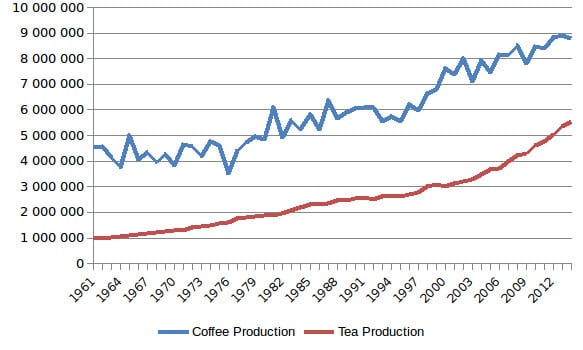

After looking on the Internet with several keywords, I found out that the available statistics on alcohol consumption were from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and expressed in terms of consumption per capita in litres of pure alcohol. Let’s put it in other words, they converted all the drinks into pure alcohol (I have no real clue how it works but the basis seemed coherent to me) and they had databases covering each year between 1961 and 2017. The earlier years were not always coherent or complete but I had a base to begin working with.

For teas, I had to answer a rather simple question: how much tea was drunk? I had access to several sets of tea related data but not a single one giving me this information.

My educated guess was that “what a country/area produced each year + what a country/area imported each year – what a country/area exported each year” was a good estimate of how much tea was available for consumption. Obviously, this is only an estimate as not all this tea is drunk each year but if you have a better idea, I am all ears.

However this was not enough as I couldn’t compare tons and litres. I needed a way to convert these available tons in litres of tea. After a lot of thought and look all around, I decided to go for 12 grams of tea per litre, which means that with 1 ton you could get 83,333 litres of tea (again if you have other figures, let me know).

The nice thing was that I had access to the same timeline as the WHO one, which made comparison and statistical analysis easier.

This is all for now but stay tuned as next time I will compare the data and try to see how they evolve over time and if there is any link between them.

Recent Comments