Sometimes economists like to develop their concepts in what seems to be a sandbox way before applying them to reality to check if they are worth anything. When I say in a sandbox way, I mean based on certain hypotheses that to other people can seem completely out of reality. But this is how it works; since economics focuses on the way economic agents interact and behave and because these economic agents are complete beings and things, you need in order to study them to “simplify” things and to see then how what you found out works in real life.

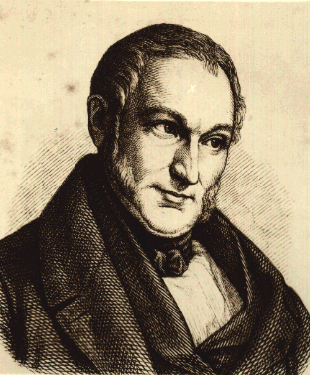

One example is the work of Johann Heinrich von Thünen, a German nineteenth century economist that developed a mathematical formula to know what was the best use (in terms of production type) for a piece of land based on the transport costs to a market and the rent a farmer could afford (based on the yield of a given product, its selling price and its costs of production). Of course there are “weaknesses” or simplifications as I said earlier. For example, the differences in transportation costs, in topography, in soil fertility or the changes in price/demand were not taken into account in this simplified but quite important model.

One example is the work of Johann Heinrich von Thünen, a German nineteenth century economist that developed a mathematical formula to know what was the best use (in terms of production type) for a piece of land based on the transport costs to a market and the rent a farmer could afford (based on the yield of a given product, its selling price and its costs of production). Of course there are “weaknesses” or simplifications as I said earlier. For example, the differences in transportation costs, in topography, in soil fertility or the changes in price/demand were not taken into account in this simplified but quite important model.

I am sure you are now wondering why I am speaking of this right now and if the economics part of teaconomics has taken control of my writings.

But not at all. You will have to be patient for a little while before seeing where I want to go.

As I said, Johann Heinrich von Thünen didn’t take into account the differences in transportation costs and their impact on the overall chain. These differences can come from three sources: differences in infrastructures, efficiency of transport companies and different means of transport but they will have different impacts on the transport chain and thus on the best place to implement such and such resources (at least in his model).

What is the link between all this and tea? The answer is in the title of the song Hit the road Jack, transport. This is the reason why colonial empires devised and created transport networks to insure that the production of the colonies (mostly commodities) would get to the mainland as quickly, as cheaply and as efficiently as possible (okay, they also wanted to get their soldiers where needed as quickly and as efficiently as possible).

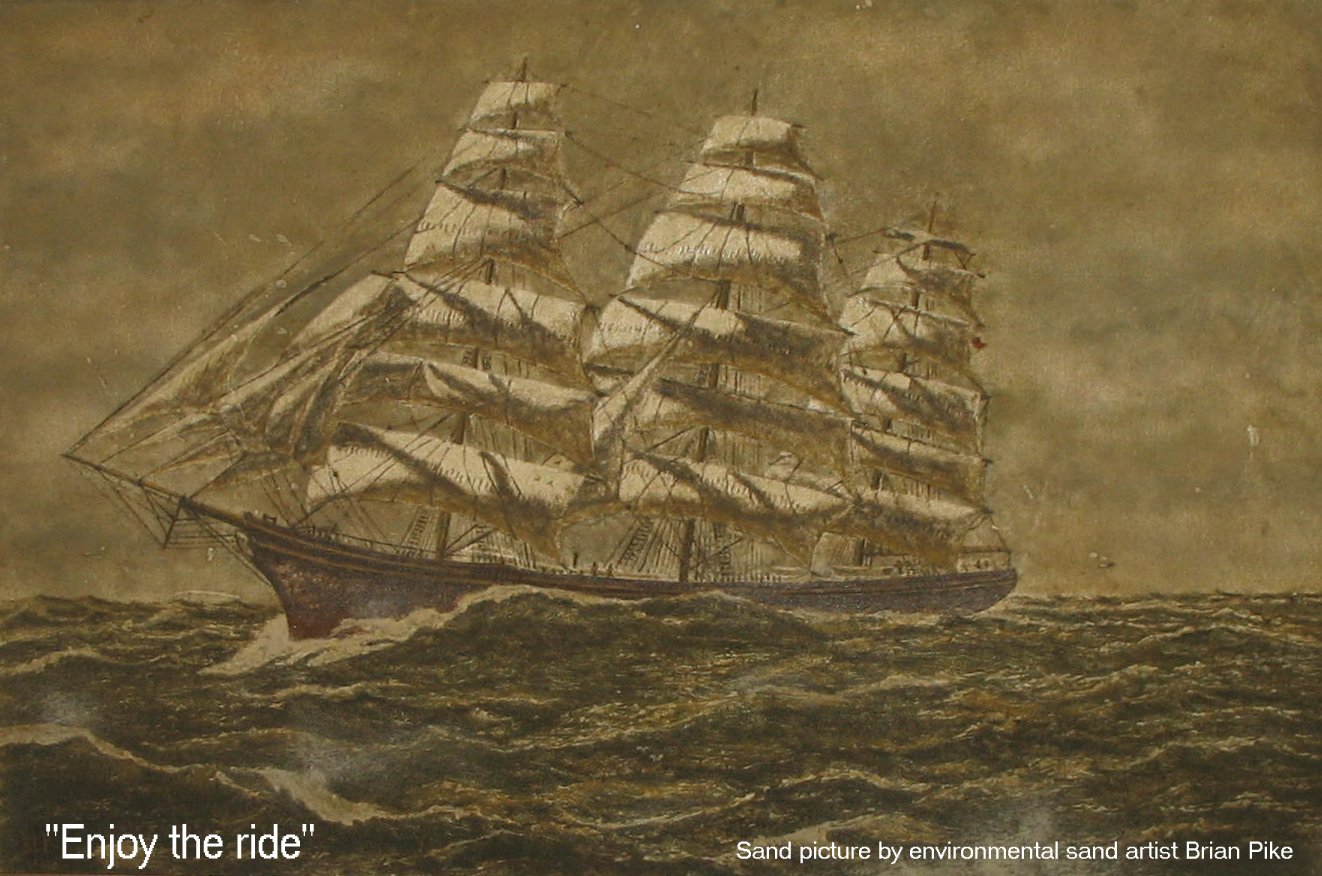

This is what was seen in tea too as earlier, you needed to get the freshest tea on market and to be the first to land in let’s say London. This is why clippers, the fastest sailing ships were built (before being becoming irrelevant because of steam and the Suez Canal (a new transport infrastructure)) and used to transport light and valuable cargo that needed to reach the ports as quickly as possible (tea, opium, people…). Today this trend is still alive for some teas (first-flush Darjeeling for example), planes are used in order to get them as fast as possible to the market.

Tea Clipper Foochow – sand painting by Brian Pike

But every journey begins with a first step. For tea, it is simple you need to get it from where the gardens/factories are to where the customers are, which means getting them out of the mountains/hills/remote locations where they are most of the time situated and then through the cities and/or the oceans. Unfortunately (or not), we are not playing in a sandbox and thus the model developed by von Thünen can’t be used right away to place tea gardens there, factories somewhere else and cities (or markets) in a third place. As with most human related things, we have to deal with how nature and humanity interacted over the centuries, creating a complicated and not always efficient network.

You will ask why does it matter? What do I as a customer get from an efficient transport system built around efficient infrastructures (one of the first steps for an efficient transport system)?

Let me tell you that the overall efficiency of any transportation system can make a lot of difference. For example, according to the World Trade Organisation World Trade Report 2004 (p.119) that quoted an article by the Economist, the poor road infrastructure in Cameroon increased the production costs of beer by 15 per cent and then you had to add the transportation costs to every place in the country. This meant that a beer costing 1 in Douala by the sea would cost 1.3 in an eastern village.

Now imagine this applied to a commodity that needs to be shipped through a country and then to another one far, far away (it seems a bit like the beginning of a fairytale, doesn’t it?). Based on the previous ratio (which might or might not be a bit too much for tea), it would mean paying tea at a much higher price. For a production process that has been refined over hundreds of years with as I said a focus since the beginning on exportation like India, it seems rather unlikely. However, it was a problem a few years ago at least in some parts of the country with two major impacts: difficulties to get supplies in and difficulties to get tea out.

Is it still the case today? I read that investments have been made with a special focus on this topic but only time and experience from people in the country will tell us how things have evolved and will evolve.

Recent Comments